The village of Kukuo at sunset.

Most Junior Fellow volunteers with EWB spend at least one week living in a village. The idea is to gain a better understanding of rural livelihoods and some of the challenges facing the poorest people in developing countries. I chose to visit the community of my friend Tuferu, the NILRIFACU rice cooperative’s store keeper. The goals of my stay were threefold:

1. Gain a better understanding of rural livelihoods and poverty in Ghana.

2. Learn more about the farmer members of the NILRIFACU rice cooperative and the services NILRIFACU provides.

3. Talk to farmers growing the new NERICA rice variety and collect data on the relative profitability of the crop. Also investigate alternatives for enhancing soil fertility, as NERICA typically requires large inputs of chemical fertilizer.

As Parker Mitchel (EWB co-CEO) recently pointed out, the good thing about trying to hit three birds with one stone is that you’re bound to take down at least one. I’d like to think I’ve done more than that, but you can judge for yourself.

Kukuo and My Hosts

The village of Kukuo is two miles outside Kumbungu, the largest centre in the Tolon/Kumbungu District. Kukuo has roughly twenty compound houses and four to five hundred residents. Although the village does not have electricity, it has the good fortune of being located on the pipeline carrying water to the regional capital of Tamale. As a result, residents have access to standpipes distributed throughout the community. Although the water looks a bit murky some days, it’s actually fairly clean and I drank it throughout my stay.

A water pipeline passes by Kukuo on its way to Tamale.

Kukuo residents have access to standpipes for water.

Tuferu has one wife and three boys aged six, nine and fourteen. His house is made up of his direct family, his parents, several of his brothers and their families and a couple of his unmarried sisters. There are twenty-four people in total. The household’s main source of income is farming. Maize and rice are the two largest crops; maize being grown primarily for consumption and rice being grown for sale. The household also grows beans, cassava, yam, bambara beans, cowpea, sorghum, millet, soybean, peppers and tomatoes.

The family plants maize outside their compound.

NERICA rice is planted in the lowland areas, further from the house.

I got to help Tuferu and his son Fatowu transplant tomatoes.

Tuferu’s family keeps livestock including goats, sheep, cattle, chickens and guinea fowl. Livestock often serve as a ‘bank account’; animals can be bought or sold as money accumulates or runs out. In addition, bull ox are used to plough fields, reducing the community’s dependence on tractors. Other households without bull ox can pay Tuferu the equivalent of fifteen Canadian dollars to plough one acre. Theft of cattle and sheep has become a serious issue in the area. Tuferu’s oldest brother sits up at night to guard the cattle with a rifle. Last year during a storm he made the mistake of going inside to sleep briefly and two of the largest bull ox were stolen. Armed thieves come in vans at night and take the stolen animals to the city to be sold.

Theft of cattle and sheep has become a serious issue in the area.

Women also play an important income generating role in the household. In addition to washing most of the clothing and preparing all the food, the women process rice and shea butter. Processing rice roughly doubles its value, but the cost of milling and transport consumes a portion of the profit. One bowl of shea butter sells for the equivalent of six Canadian dollars at the market in Kumbungu. Shea butter is used both in Ghana and internationally for the production of soap, cosmetics and chocolate. Although I didn’t ask, I estimate the household produces three to five bowls a week. They work on a weekly cycle, the whole process taking seven days, at which point they begin again.

Preparing TZ (made from maize flower) for the entire household.

Rice processing:

Rice is parboiled to soften the husk and make it easier to mill.

Once rice is parboiled, it is spread out to dry in the sun.

After milling the rice is winnowed by dropping it through the air and allowing the wind to blow the chaff (husk) away.

Shea Nut Processing:

Shea nuts are collected from wild shea trees and carried back to the house by women on their heads.

The outer green fruit of the shea nut can also be eaten and is quite sweet.

The shea nut must be boiled to soften the shell.

After boiling the shea nuts are dried.

The shells are cracked with a wooden paddle.

The shells are removed and the inner core is taken to the mill. It comes out looking like melted chocolate.

It is left and hardens into a paste.

The paste is whipped by hand.

After whipping the 'fluffy part' is removed and later melts back into a liquid (ok, I'm not exactly clear on this part).

The shea is boiled again to make shea butter.

Finally it is collected in bowls to take to the market. The yellow colour is from adding some sort of tree leaf.

Although very few of the household’s members spoke English, I was impressed by how much value they placed on education. Tuferu’s oldest son, Fatowu, is at the junior secondary school level. Despite having to ride his bicycle an hour each way to school, Fatowu says that he never misses class. Even during the rainy season, when most farming takes places, he only goes to the field in the afternoon once he has returned from school.

Fatowu never misses school, even during the peak farming season.

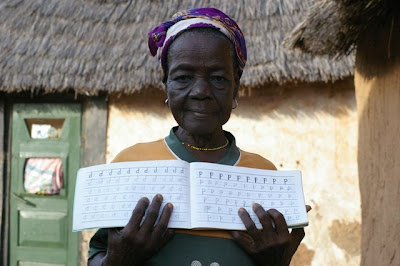

Fatowu’s older family members did not have the same opportunities he has and few have completed primary school. Fatowu says that often the primary school teachers will just sit around and talk, rather than teaching. I get a sense that this is common in most primary schools in Ghana, children seem to spend more time ‘playing’ than anything else and it shows. Although Fatowu has only completed his first year of secondary school, he is already learning to use a computer and has a basic understanding of world geography. “Last year”, he tells me, “I would not have been able to speak English to you like this”. Most of the large number of Ghanaians who do not go further than primary school will never learning how to read, speak fluent English (Ghana’s only national language) or be able to point to Ghana on a map. Tuferu’s sixty-year-old mother, Sanatu, proves it’s never too late to learn though, as she holds up the workbook in which she has been practicing her letters.

Sanatu, sixty, proves it's never too late to learn.

The NILRIFACU Rice Cooperative

In an effort to learn more about how NILRIFACU’s members see the cooperative, I tried asking Tuferu what he thinks of the group. He said that the cooperative is good because it allows him to purchase seed and fertilizer and coordinate loans with the bank for his entire community. It would be very difficult for farmers to obtain seed and fertilizer individually and banks only give loans to farmer groups. This perception of NILRIFACU is somewhat different than the one I went in with. Because the cooperative has a marketing fund to buy and sell rice, it could in theory be run as a profitable business. As I near the end of my placement, I’m starting to question whether this is really what the executives want to be doing and if it will ever be a viable reality. Regardless, I sense there’s a disconnect between the NGO that established the group and those who are now responsible for running it.

NILRIFACU has a store house in Kukuo where rice is kept from harvest time until when it is sold later in the year.

NERICA Rice and Soil Fertility

Tuferu is a good farmer. In 2003 he was awarded Best Farmer in the District by the Ministry of Food and Agriculture and says he hopes to win it again this year. When officials began the NERICA rice program he was a natural choice to be one of the pioneer farmers.

Tuferu was awarded Best Farmer of the Year in 2003.

I asked Tuferu why he and other farmers in his community grow NERICA rice. From what I gathered, part of the reason stems from the incentives put in place by those promoting the rice including free seed, fertilizer on credit and guaranteed market access. This is somewhat troubling, as these incentive programs are scheduled to end in the next couple years. Tuferu says that while NERICA rice gets lower yields than other rice varieties, he likes that it matures earlier (90 days instead of 120 days) and requires less water. Because NERICA can be harvested a month before other rice varieties, it is less susceptible to late season droughts. He also said that people enjoy the taste of NERICA more than other varieties. I had the opportunity to try some on my last night in the village but despite having eaten more rice this summer than the rest of my life combined, I still hadn’t developed a sophisticated enough pallet to detect the difference.

NERICA rice.

Perhaps the most interesting thing I discovered in Kukuo was the use of compost and animal dung to enhance soil fertility. Each house digs holes about two meters in diameter in which they deposit the leaves and wastes from rice and shea nut processing. The compost is covered with grass and sticks and allowed to incubate for two to four months. They also tie up all the animals during the rainy (and farming) season which has the benefit of keeping the animals from eating the crops, but also allows for the collection of manure. Other communities I’ve observed allow animals to roam free all year round, which not only requires the construction of fences around crops to protect them, but also makes it impossible to collect manure. Farmers in Kukuo transport compost and manure to their fields with bicycles (if they have) or on their heads.

Waste from rice and shea nut processing is deposited in compost holes. The compost is later transported to fields by bicycle or on farmers' heads.

Goats, sheep and cattle are tied up during the farming season allowing for the collection of manure and eliminating the need to construct fences around the crops.

Tuferu’s household used compost and animal dung on their maize. I had a chance to measure and compare the productivity of two maize plots during my stay. Based on my rough measurements and what Tuferu's told me the yields of each have been, the plot on which the compost is applied with less than half the chemical fertilizer yields almost twice as much grain per acre as the plot in which the full recommended quantity of chemical fertilizer is applied.

The results are an approximation at best and there are doubtlessly other factors at play, but I think they indicate an important fact: there are viable alternatives to the use of chemical fertilizers. I asked Tuferu what the greatest obstacles are to increasing the use of compost and manure. He indicated that labour is a major constraint; transporting compost is time consuming. With a 4x4 truck it wouldn’t be so hard he explained, but most farmers cannot afford vehicles. Given the government’s subsidy of chemical fertilizers this year, I’m questioning whether there aren’t other options for boosting agricultural production in the country. Perhaps helping farmers with transport of compost and manure would be more productive? Talking to farmers from other communities, I get the sense that knowledge about composting is lacking as well. Should agricultural extension agents make this a stronger focus?

Final Thoughts

While my stay in Kukuo was extremely educational and I enjoyed aspects of it, it was also very challenging. When I first arrived Tuferu told me that he was “preparing to come to my country”. To put things in perspective, Tuferu doesn’t know where “my country” is, nor does he have the financial means to travel there or the characteristics that would make it possible for him to obtain a visa. When I tried to explain these obstacles, he refuted that he would go to his politicians or an NGO and get them to help him. He explained that he only wants to come for a short time to collect some money and then return.

These types of conversations continued throughout the week and my frustration mounted. One night we almost ended up shouting at each other. Several things bothered me and still bother me. Firstly, he’s under the impression that everyone in the western world is rich. He thinks that if he can only get there, he’ll be able to pick up money off the street and live like a king. He has no idea how hard it is for new immigrants. Coming to Ghana I’ve got a taste of what it’s like to enter a new culture where everything from the food to the toilets is different. If somehow he were to come to Canada he’d likely work at McDonalds, have drunk teenagers yell at him, miss his family and not be able to find TZ anywhere. He’d go from being a knowledgeable and respected member of his community to another struggling immigrant.

So in part I’m frustrated by his stubbornness and what he doesn’t know he doesn’t know. I’m frustrated by how common his attitude is; how so many Ghanaians live for a dream that so few will ever realize, a dream that doesn’t even exist as they imagine it. Not only does it make me sad for them, but it makes me angry because I feel like it removes the incentive and the responsibility people have to improve their own condition. At the same time, Tuferu makes some undeniable points: life in Canada is easier for most people, there are more opportunities. How can I say he shouldn’t dream of having the same things I have? And so I continue to be frustrated by the situation; by the hypocrisy of my own frustration. Maybe it’s not my place to comment. I’ve met numerous Ghanaians who are committed to creating change in their own country and have no desire to leave; perhaps they’re the ones who have to do the real convincing.

Frustrations aside, there’s nothing quite like lying under the stars on a warm African night listening to Dagbani music crackle through the radio. I asked Fatowu what he believed the stars were. He said only god knows, but that each person has a star and that when they die their star is gone as well. There’s something comforting in that; that you can look up and see the whole world in the sky. It wasn’t an easy week, but it was one that I’ll remember for a long time - especially when I look up at the stars.

It was a memorable week.

3 comments:

as always, great pictures and great insight, Sam.

can't wait to hear all about the second half in just a couple of days!

Hi Sam - great photos, great blog. I especially love the pic showing your sandal tan lines!

We are currently forming a 'bloggers in Ghana' group and it would be great if you and your other colleagues (in your blogroll) who are in Ghana would join as well. We are trying to gather a wide range of bloggers here. Let me know if tyou are interested and I'll keep you updated.

my e-mail is holli@shiloh410.com

I'm from Toronto and I've been living and working in Accra for 11 years. I blog about life here as well...

Hope to hear from yuo soon.

Cheers

Holli

looking good my friend, and another great post

Post a Comment